01.11.2016 | The Jena Codex is a unique monument of Czech literature and one of the most precious manuscripts stored in the collections of the National Museum. It is important not only for its beautiful illuminations, but also because it is a testimony of the Hussite period, which was one of the key periods in Czech history.

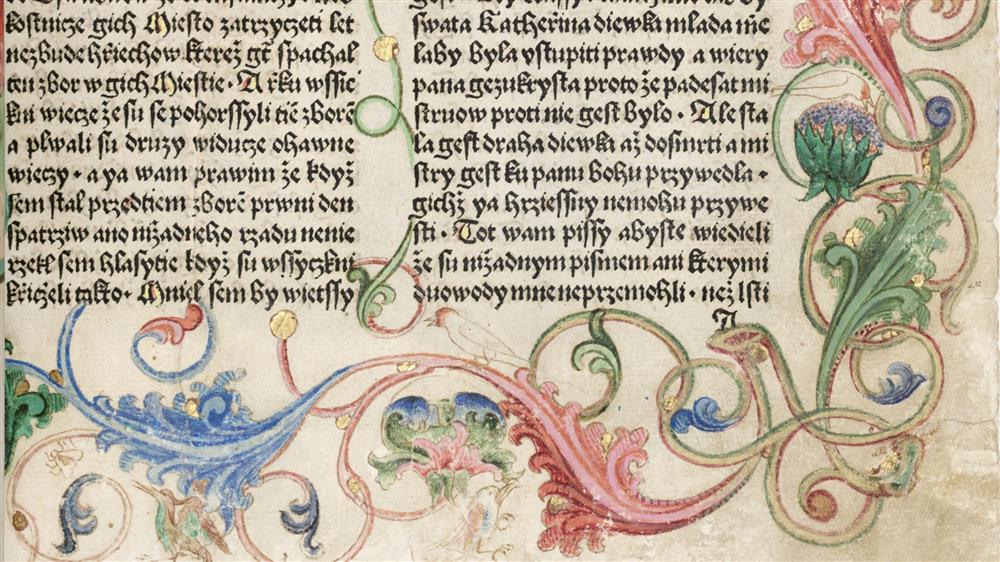

The Codex stored in the National Museum’s department of manuscripts and early prints originated in the late 15th and early 16th century Czech Lands. The impetus for the drawing of this document came from the Utraquist Bohuslav of Čechtice. The manuscript bears rich and extensive illumination. In some parts, the pictorial decorations dominate the text. The manuscript primarily contains theological treatises that are to highlight the discrepancy between the early Church and the Church of the time of Master John Huss. The illuminations depict, for example, the clergy’s dissolute lifestyle, or criticise the selling of indulgencies. Almost the entire Codex is written in Czech, with only a small part in Latin.

The manuscript is not the work of a single man. Several scribes participated in its writing. The illuminations too were the work of several people, belonging to a 16th century illumination workshop led by Janíček Zmiletý of Písek, to whom the most beautiful illuminations are attributed. It was standard practice in illumination workshops for the leading artist to create the most important illuminations and leave the others to his colleagues. Several painters might have been involved in creating one image. One painter might have worked on the borders, for example, while another concentrated on the background. It is assumed that several works similar to the Jena Codex were created in the 15th century. However, only one more manuscript comparable in its content has survived to this day - the Göttingen Codex. Although the decorations of the Jena Codex are richer and of better quality than those of the Göttingen Codex, what both works have in common is satirical text directed against the state of the contemporary Church. The figurative scenes are very appropriate to the text.

Under so far unknown circumstances, the Jena Codex came to Germany in the second half of the 16th century, possibly as a gift to Martin Luther. What is certain, though, is that it arrived in the city Jena, where it was deposited at the local university library – hence its name.

Although the manuscript was outside the country for a long time, it was not forgotten. In the 18th century, Josef Dobrovský, who studied the manuscript during his journeys abroad, renewed the interest in the Codex in the Czech environment. He pointed out this important work of Czech literature to Pavel Josef Šafařík, who subsequently created a transcript of almost the entire manuscript. However, the Czech Revivalists were not the only ones fascinated by the manuscript. The German poet Johann Wolfgang Goethe, at the time a curator of the University of Jena, also showed great interest in the Jena Codex. He even sent copies of some of the illuminations with Hussite iconography to Prague.

The manuscript returned to Bohemia only in the early 20th century, when it was lent for the purposes of study. It only finally came to stay in Prague permanently in 1951, when the president of the German Democratic Republic, Wilhelm Pieck, presented it as a gift to the Czechoslovak president Klement Gottwald. Since then, the Codex has been stored in the Library of the National Museum. The manuscript attracted the attention of experts and the media, thanks to which it was introduced to public awareness.

However, the great interest of experts and the media in the 1950s and 1960s had a very negative effect on the Codex. The constant opening, filming and photographing worsened the already bad condition in which it was returned to Prague. In the end, the Codex had to be restored and preserved. For many years, the manuscript was damaged by dirt, dampness and the acidity of the ink. Great damage was done by repairs with plastic foil conducted while it was still in Germany. In the mid-1980s, the manuscript underwent complete restoration, which helped to bring it nearer to its original state.

The restorers started work after several years of obstructions. They removed earlier repairs, reintegrated the individual pages (called folia), revived its colours by sucking away the dirt, mended pages with pulp filling and paired the folia so that the manuscript could later be bound. Here, the experts had to solve the problem of the pages overlapping the binding, due to which, even earlier, the manuscript was repeatedly damaged. In the end, this problem was solved by the appropriate adjustment to the binding boards. Five years from the beginning of the preparations, the restoration work was finally finished. This unique literary work regained its former splendour.

(EK)